A Hell of Heaven

Investigating innovation and degradation in Contemporary Art (and where to go from here)

On October 23rd, 2023, the city of Vienna, Austria unveiled a new fountain which purported to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the city’s modern water system. Titled ‘WirWasser,’ the €1.8M fountain reportedly came in under its original €2M budget and, as the mayor pointed out, was completed in just eight months. Indeed, by the looks of it.

If you have spent any amount of time on social media in recent memory, you will recognize the pattern. Some staggeringly expensive, manifestly wretched piece of municipal art is unveiled. Public outcry erupts over what many see as the exorbitant expense and questionable aesthetic value of these works. Common are the exclamations of righteous disbelief at taxpayer expenses and disdainful comparisons of these artworks to that of mere children. Others still will lament the imminent fall of Western civilization as evidenced by the profoundly cynical and ugly artwork that is allowed to be produced and displayed in public spaces with unchecked abandon.

None of this is very new; publicly funded “ugly” art is so common it borders on cliché at this point, but it seems in our current era to tread ever further into the intentionally obscene. What we are left with is an environment that is thoroughly depressing, and a populace that becomes more and more apathetic to the travesty.

Contemporary art in exhibition settings is hardly different either. Many will dismiss contemporary art as a poorly disguised vehicle for money-laundering (a simplistic and cynical take, in my opinion, but perhaps there is some truth to this, in some cases). My opinion lies somewhere in the middle, and more interestingly, I think there is a deeper truth that can be revealed by asking these questions with sincerity and without dismissal.

How did we get here? What does this mean as a reflection of our collective psyche, and what is there to be done to reclaim a balance between the challenging, the provocative, and the beautiful?

How It Started

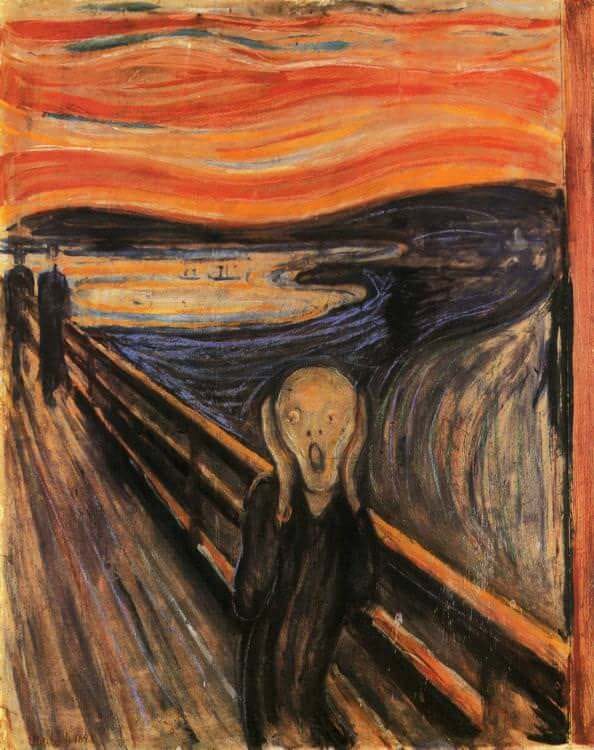

The genealogy of ugly modern art can be roughly traced back to the 19th century. This era saw a gradual yet profound shift in the way humanity understood its place in the universe, significantly influenced by the Industrial Revolution, advancement of scientific thought, and a diminishing reliance on traditional religious narratives. Before, the role and rules of art were significantly influenced by academic institutions, which upheld classical standards and generally discouraged emotional expressiveness and individualism. Artists worked primarily in service to the public, the state, the church, and wealthy patrons, and as a result, art served a very specific purpose. The Enlightenment, preceding the Romantic period, had already set in motion a preference for empirical evidence and rational thinking over traditional beliefs and superstitions. Scientific discoveries began to offer explanations for phenomena that were previously attributed to the divine; this led to a sort of naturalistic dissonance in which many began to feel adrift in an entropic universe. The transition from a world imbued with religious certainty to one increasingly oriented around science and empirical observation, marked a profound shift in human consciousness and led to a crisis of meaning.

Romantic artists and thinkers often responded to this crisis by turning towards emotion, nature, and the sublime. They celebrated imagination over empirical evidence, often focusing on themes like inner turmoil, the majesty of nature, heroism, and nationalism. Meanwhile, technological advancements like photography dramatically shifted the artist's role, freeing them from the need to replicate reality and inspiring a focus on subjective, abstract, and emotional expression. This period saw artists transitioning from being servants of the public, creating artworks commissioned or broadly catered to popular taste, to becoming self-styled visionaries, imbued with the mission to share their profound insights and unique perspectives.

As an artist, I'm inclined to see the shift in creative consciousness as fundamentally positive. This change opened doors to a richer and more diverse exploration of human experience and creativity. It created an environment where, a century and change later, I could build a career centered on self-expression, rather than conforming to the dictates of the state or popular taste. However, the relentless pace of progress also has its pitfalls. In the case of art, this paved the way for the rather navel-gazing endeavor of Modernism, which was to uncover the truth of “what Art is,” at the expense of itself.

The Slippery Slope

The late 19th century marked a dramatic turn. Modernist artists, racked with ennui, began a systematic exploration of art's components, often challenging or outright rejecting them. This break from tradition was driven by several factors: a growing naturalism that left some feeling isolated in an empty, godless universe; philosophical skepticism and irrationalism that undermined trust in perception and reason; evolutionary and entropic theories presenting a bleak view of human nature and destiny; political disillusionment; and fears that technological advancements might ultimately dehumanize or destroy humanity. These diverse influences drove the modernists to an intense anxiety, which spurred the movement to redefine the essence of art. Art had to be a quest for truth above all, and the truth was ugly.

Marcel Duchamp capped this entire era with his 1917 work "Fountain," with which all of us are familiar. The work consists of a standard porcelain urinal, which Duchamp purchased from a plumbing supply store. He laid the urinal on its back, signed it "R. Mutt 1917," and submitted it for exhibition to the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The piece—initially rejected by the committee, despite the Society's claim that all works by paying artists would be accepted—symbolized a fundamental shift in modern art: from being a creative and technical endeavor to a philosophical inquiry. Duchamp recognized art's historical power to inspire and elevate human experience but used "Fountain" to question the essence of art and the role of the artist. He suggested that art had become more about intellectual exploration than aesthetic experience, reducing the artist to a concept rather than a creator of aesthetic value.

Duchamp's perspective highlighted that modernism, in its quest to understand art, often lost sight of its traditional values, leading to a state where art risked becoming meaningless. By the 1960s, this existential crisis within modern art was evident, as reflected in the views of artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, who echoed the sentiment that art had become devoid of substantive content and had reached a conceptual dead end. Duchamp's critique, therefore, represented a crucial turning point, emphasizing the philosophical over the artistic and leading to a reevaluation of what constitutes art. By the 1960’s, Modernists found that they had nothing left to say on the matter, if indeed anything was worth saying at all.

L.H.O.O.Q.

One would think that after the decline of Modernism there might be nowhere to go but up. Alas, Postmodernism emerged as a response. Drawing from the intellectual and cultural milieu of the late 1960s and 1970s, Postmodernism drew on the Existentialist notion of life's inherent absurdity, questioning the search for absolute meaning in a seemingly random universe; the limitations of Positivism, which sought to distill complex social realities into rigid scientific laws; and the disintegration of the New Left, a political wave that pushed for a variety of progressive causes and forms of socialism but began to lose cohesion and influence by the 1970s. It aligned with thinkers like Thomas Kuhn, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, embracing themes of antirealism, deconstruction, and criticism of Western culture. With a decidedly left-wing orientation, postmodernism embodied both nihilistic and revolutionary elements, resonating with the post-war, post-empire zeitgeist in the West. Over time, its initially predominant deconstructive aspects gradually gave way to a focus on revolutionary identity politics, though the nihilistic foundations remain a fundamental aspect of the movement.

The Postmodernists deliberately avoided a return to classicism, romanticism, or traditional realism in art. Postmodernism reintroduced content that was self-referential and ironic, rejecting realism and treating concepts like reality and nature as social constructs. Postmodernists preferred content that focused on important themes of power, wealth, and justice, even as it focused solely on grotesque manifestations and negative commentary. Where once the aim was to use provocation as a tool for intellectual or emotional engagement, the focus now turned to evoking immediate, often negative, visceral responses. This change reflects an unfortunate yet logical progression—from using art as a means of communication or expression that challenges viewers to think or feel, to using it as a vehicle for creating shock and discomfort. Thus by the 80’s and 90’s, Postmodern art had taken a swan dive into a hedonistic preoccupation with blood, urine, feces, sexual fetishes, bestiality, and pedophilia.

A product of the influence of these Postmodern ideas, artists today often feel compelled to move beyond creating aesthetically pleasing works to instead focus on challenging and provoking conventional wisdom. Beauty is seen as a frivolity when compared to the artist's commitment to being provocative. In this new paradigm, the value of art is measured not by the depth of the conversation it sparks, but by the intensity of the reaction it elicits, regardless of the quality or constructiveness of that reaction. In this context, to the extent an artist has a moral duty, his duty is to create art that disgusts.

You Get What You Pay For

While discussing the devolution of art into forms that prioritize shock over substance, it's important to acknowledge that not all modern art follows this trend; some branches on the family tree have produced influential and celebrated artists. The spirit of subversion is a key element in much street art and graffiti, which frequently includes social, political, and cultural commentary, and paved the way for contemporary muralism. The challenge to traditional art boundaries, blurring of high and low culture, playfulness and irreverence that characterized some modern art movements, has made art fun and accessible to broad audiences. All of this has made it possible for artists like me to actually make a viable living what we do. It’s important to understand, though, that the ugliness in much of today’s art did not emerge in a vacuum; rather, it's the product of a lineage that traces back through the developments and shifts in the continuum of art history. Lamenting the state of it as evidence of “the decline of the West,” or just dismissing it out of hand as some kind of cynical conspiracy, disempowers us from being able to do anything about it. We should thus not be surprised if things only continue to get worse.

‘WirWasser,’ and others like it, owes its existence to the inherently contradictory and irrational foundations of Postmodern thought. This school of thought, as it permeates today, rejects wholesale the existence of a stable reality and reliable knowledge, viewing objective reality as a bourgeois, Western male construct. In this view, shared humanity and individuality are illusions, and people are categorized as oppressors or victims based on social identity. Postmodernists challenge any universal systems of thought that claim to explain the world, its laws, moral truths, historical progress, and human nature, applicable to all people across all times and places. The movement tortures empirical evidence and dominant cultural concepts like science and reason, creating a cycle of continuous debate and reinterpretation.

In many popular dystopian narratives—1984, The Hunger Games, The Handmaid’s Tale… name your favorite—the reader empathizes with an outlier, someone who is horrified by societal norms that others consider normal or even ideal. This narrative device serves as a reflection on how easily people can adapt to or become complicit in systems that might be deemed oppressive or dystopian by an impartial observer, underscoring the conflict between individual consciousness and societal conformity. The pervasiveness of our current state—with its full-throated cultural and institutional support—gives credence to the notion that people might inherently lean towards dystopian conditions. This echoes what C.S. Lewis explores in The Great Divorce, where the damned find comfort in hell and cannot endure the reality outside of it. If the State actively promotes art that is perceived as ugly or demoralizing, this could contribute to an overall atmosphere of disempowerment and malaise. Such art could serve to normalize a bleak or hopeless view of the world, subtly influencing people to accept and even expect this in their everyday lives. For whatever reason, they may even convince themselves they like it.

The central question here is how to recover from this state, especially when faith and belief systems, once central to human civilization and individual identity, have eroded. The challenge is immense: once faith dissipates, rekindling it—either in an individual or society—is a daunting task. It’s not easy to rationalize your way back into belief, and creating faith from a void is arguably even harder.

Is there a way through this crisis? The answer might lie in recognizing the value and impact of these real human experiences – acknowledging the role of love, death, and the myriad emotions in between, in shaping our lives and worldviews. Embracing these elements could lead to a re-engagement with the world as it is, rather than as it's depicted in virtual or dystopian narratives. However, the journey towards this re-engagement is intricate and deeply personal, requiring a collective shift in perspective that values authenticity, connection, and perhaps a renewed understanding of faith and meaning.

Modernity has led us to unprecedented wealth and comfort which we in the West take for granted today. The Postmodern infiltration into most western institutions has fomented a precarious backlash in which the enemies of modernity are split into two fringe factions: the Postmoderns who continue to destroy for the sake of it, and the “Trads” who wish to forsake modernity altogether—along with the liberal values on which it blames the Current State of Affairs—and to revert to some form of medieval pre-enlightenment social order. Both of these factions, if they got their way, would be more destructive than any of us take for granted. To the extent that art reflects culture, the answer may lie in our purpose and intention with which we do our craft.

While art should certainly confront and critique the problems in the world when necessary, the issue lies with the overwhelming negativity and destructiveness that has characterized much of the art world since 1970. There remains a troubling lack of discernment among artists over when and how these critiques should be implemented in order to be most impactful. Embracing a more balanced approach to our work that highlights human relations, dignity, courage, and the joy of existence, can and does lead to positive social transformation.

Art shines most brightly when it reflects the human being’s commitment to life. I am seeing, and support, an evolution in Contemporary art to merge the insights of Modernism while re-embracing narrative, emotion, and beauty. The melding of traditional techniques with new mediums and messages, along with the resurgence of craftsmanship in various art forms, represents a respectful acknowledgment of our patrons’ intelligence and emotional depth. Rather than demean and alienate our audience for some kind of perverse self-referential reward, this careful balance allows artists to address important social topics in a way that is both impactful and considerate, honoring our fellows’ ability to appreciate complexity and nuance. Such an approach not only conveys messages effectively but also fosters deeper, more meaningful engagement with art, nurturing a space ripe for constructive dialogue. Ultimately, this shift can transform art into a powerful catalyst for a better world.