Cattelan’s banana is back in the news again. Yes, that banana. The controversial work by the Italian artist that first made headlines in 2019 just sold again at Sotheby’s—this time for $6.2 million. Le sigh.

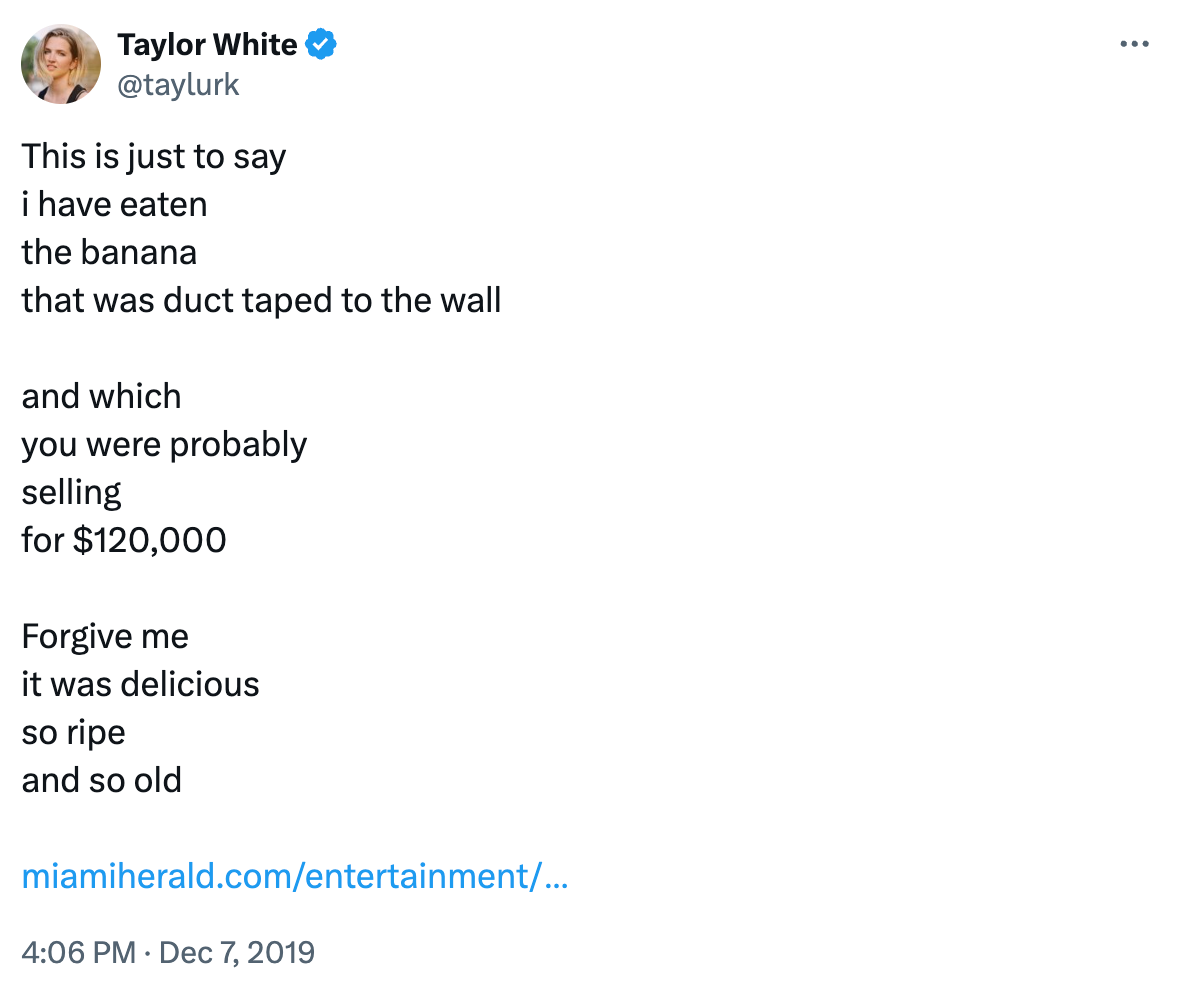

The world’s most infamous edible fruit first appeared duct taped to a wall in Perrotin gallery’s booth at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2019. I was there. It was called “Comedian,” and it sold for $120,000 (and then again for $150,000, but not before someone ate it.) At the time it was an absurd joke, a conversation starter, and yes, obviously a photo op.

The responses were swift, predictable, and loud. It’s a critique of the art market’s absurdity. It’s a symbol of wealth inequality. It’s money laundering. It’s stupid! All true, and none of it surprising. Yes, Comedian allegedly critiques the absurdities of the art market, wealth inequality, and commodification of meaning. And it made some prick artist richer by hundreds of thousands of dollars. And as designed, it made headlines around the world, unifying us all in our collective annoyance.

But this is not new—these critiques have been made for decades. From Duchamp’s Fountain to Warhol’s soup cans, the art world has toyed with concepts of value, originality, and consumer culture. Comedian is simply the latest iteration, rehashing well-worn territory but wrapped in just enough absurdity to reignite public discourse. Even casual observers who know little about art recognize this critique. The banana doesn’t challenge anyone’s assumptions—it confirms them.

And yet, this familiarity is what makes the banana so effective. It’s the fruit (pun intended) of an era of social media and memes—a perfect shorthand for the contradictions of the art world and an instantly recognizable icon for conversations about meaning and money. The banana doesn’t have to be “original” to make its point. In fact, its lack of originality reinforces its critique: even the critiques are recycled. The banana is a visual meme, easy to grasp, easy to replicate, and impossible to ignore.

But Cattelan’s work, while provocative, adds little to conversations already happening in and outside the art world. The real story lies not in the artwork or the criticism but in the audience’s predictable response. Why do people keep engaging with this same critique over and over again? Cattelan’s banana doesn’t aim to teach us something new about art or society—it’s an object lesson in how these critiques are endlessly reproduced and consumed. The joke is that everyone involved—artist, collector, critic, audience—is complicit in the absurdity. And it’s one we can’t stop telling.

If Comedian is such an insipid dreck (it is), then why does it thrive? It does so because the art world is a feedback loop—a self-contained ecosystem where critique, spectacle, and market dynamics feed into one another, endlessly reinforcing the same patterns. The art world, at its highest echelons, operates less like an open forum for creativity and more like a closed circuit, where value is dictated by an elite network of galleries, auction houses, and collectors. Within this system, the power of a work like Comedian doesn’t come from its artistic innovation or craftsmanship but from its ability to generate spectacle. It thrives not because it challenges the art world but because it perfectly conforms to it. Comedian embodies what the system rewards: a work that is provocative but safe, controversial but easy to digest. It’s a commodity masquerading as a critique, its value inflated not by intrinsic merit but by its proximity to cultural and economic power. The banana becomes valuable because it plays the game better than most.

This is not a critique of Cattelan alone—it’s a critique of the system that ensures Comedian’s success. By design, the art world’s mechanisms of value production rely on exclusivity and spectacle. The more attention-grabbing or outrageous a work, the more it becomes a magnet for headlines, Instagram posts, and thinkpieces. This media attention fuels market interest, which in turn drives up the price tag, creating a cycle where the critique itself becomes a commodity. The banana’s critique of the art world as absurd, elitist, and detached is not subversive—it’s the very fuel of its own success. Its audacity becomes a kind of social capital, traded among insiders who understand the game and can afford to play it. Comedian may symbolize the self-referential nature of the art world, where the artwork, the spectacle, and the backlash are all expected parts of the process. It’s not about the banana but the system that ensures it will succeed.

If Comedian critiques the art world’s absurdity, it’s not just the elites who are implicated—it’s all of us. The banana succeeds because it pulls the audience into its orbit, making us complicit in the very spectacle we claim to criticize. Whether we laugh, rage, or shrug, our reaction fuels the machine, ensuring its relevance and reinforcing its value. This is the feedback loop extended to the audience: we see the absurdity, we recognize it, and yet we continue to engage. We share memes, write think pieces, and argue about its meaning (or lack thereof). In doing so, we become participants in the system we ostensibly reject. The banana isn’t just about the absurdity of the art world; it’s about our inability—or unwillingness—to step outside the cycle of critique and consumption.

What makes this even more disquieting is the sense of resignation that underpins our reactions. Everyone knows what Comedian represents: wealth inequality, the commodification of art, the performative nature of cultural critique, the sense that the art world is mostly a sham. But this familiarity has bred a kind of numbness. We’ve seen it all before, and yet we act as if the banana is something new, as if this time, the critique might change something.

The truth is, it won’t. The banana is a mirror reflecting a society stuck in a cycle of irony and cynicism, where even the sharpest critiques are quickly absorbed and neutralized. It’s not just the art world that’s trapped in this loop—it’s all of us. We’re so accustomed to the spectacle that we can’t imagine a world without it. Instead of rejecting the game, we play along, pretending that our knowing laughter is a form of resistance when, in reality, it’s just another currency in the economy of attention.

This collective resignation is perhaps the banana’s most profound revelation. It doesn’t challenge us to think differently; it confirms what we already know and dares us to look away. The joke, ultimately, is on all of us—not because we don’t understand the joke, but because we understand it so well and still choose to stay in the game.

In this sense, the banana transcends itself as a commentary on the art world. It’s a symbol of our broader cultural malaise, where everything—art, politics, even outrage—is reduced to a consumable moment. We laugh, we share, we move on, and the system continues unabated. The banana’s final punchline is this: It’s not that art has become meaningless—it’s that we’ve learned to live comfortably with the meaninglessness.

If Comedian shows us anything, it’s that the game of contemporary art—its critiques, its spectacles, its price tags—is not for us. The banana taped to the wall may be a clever joke, but it’s a joke shared among an elite few, played out in a closed system that benefits those already in power. For most artists and audiences, this system is not just inaccessible—it’s irrelevant.

As an optimist, this is what gives me hope. The spectacle of Comedian only holds power if we believe that this is what art must be: an endless cycle of irony, detachment, and commodification. But art can—and should—be so much more. It can be about connection, about truth, about beauty. It can be a way to reflect the human experience, not just the absurdity of a market-driven world. We may not stand to earn $6.2 million for our work, but we were never going to in the first place.

The world doesn’t need more spectacle. It needs art that speaks to the human condition, that fosters connection, that makes life richer and more bearable. It needs artists willing to risk sincerity, even in a culture that often rewards detachment. It needs artists willing to revoke their attention—and their envy—from the spectacle of the elite art world and refocus on creating work that matters to real people. The true power of art isn’t in the approval of auction houses or the headlines it generates, but in the lives it touches and the communities it sustains.

Bananas come and bananas go. We have more important work to do: building an ecosystem of art that rewards sincerity, sustains livelihoods, and brings people together. When we shift our focus away from spectacle and toward connection, we reclaim the purpose of art—not as a game for the few, but as a gift for the many.

Thank you for posting these words. ☮️

Hi Taylor

This was an amazing article!

You are my kind of artist!!!